In functional programming, a monad is a structure that represents computations defined as sequences of steps. A type with a monad structure defines what it means to chain operations, or nest functions of that type together. This allows the programmer to build pipelines that process data in steps, in which each action is decorated with additional processing rules provided by the monad.[1] As such, monads have been described as "programmable semicolons"; a semicolon is the operator used to chain together individual statements in many imperative programming languages,[1] thus the expression implies that extra code will be executed between the statements in the pipeline. Monads have also been explained with a physical metaphor as assembly lines, where a conveyor belt transports data between functional units that transform it one step at a time.[2] They can also be seen as a functional design pattern to build generic types.[3]

Purely functional programs can use monads to structure procedures that include sequenced operations like those found in structured programming.[4][5] Many common programming concepts can be described in terms of a monad structure, including side effects such as input/output, variable assignment, exception handling,parsing, nondeterminism, concurrency, and continuations. This allows these concepts to be defined in a purely functional manner, without major extensions to the language's semantics. Languages like Haskell provide monads in the standard core, allowing programmers to reuse large parts of their formal definition and apply in many different libraries the same interfaces for combining functions.[6]

Formally, a monad consists of a type constructor M and two operations, bind and return (where return is often also called unit). The operations must fulfill several properties to allow the correct composition of monadicfunctions (i.e. functions that use values from the monad as their arguments or return value). The returnoperation takes a value from a plain type and puts it into a monadic container using the constructor, creating amonadic value. The bind operation performs the reverse process, extracting the original value from the container and passing it to the associated next function in the pipeline, possibly with additional checks and transformations. Because a monad can insert additional operations around a program's domain logic, monads can be considered a sort of aspect-oriented programming.[7] The domain logic can be defined by the application programmer in the pipeline, while required aside bookkeeping operations can be handled by a pre-defined monad built in advance.

The name and concept comes from the eponymous concept (monad) in category theory, where monads are one particular kind of functor, a mapping between categories; although the term monad in functional programming contexts is usually used with a meaning corresponding to that of the term strong monad in category theory.[8]

History[edit]

The concept of monad programming appeared in the 1980s in the programming language Opal even though it was called "commands" and never formally specified.[citation needed]

Eugenio Moggi first described the general use of monads to structure programs in 1991.[8] Several people built on his work, including programming language researchers Philip Wadler and Simon Peyton Jones (both of whom were involved in the specification of Haskell). Early versions of Haskell used a problematic "lazy list" model for I/O, and Haskell 1.3 introduced monads as a more flexible way to combine I/O with lazy evaluation.

In addition to I/O, programming language researchers and Haskell library designers have successfully applied monads to topics including parsers and programming language interpreters. The concept of monads along with the Haskell do-notation for them has also been generalized to form applicative functors and arrows.

For a long time, Haskell and its derivatives have been the only major users of monads in programming. There also exist formulations in Scheme, Perl, Python, Racket, Clojure and Scala, and monads have been an option in the design of a new ML standard. Recently F# has included a feature called computation expressions orworkflows, which are an attempt to introduce monadic constructs within a syntax more palatable to programmers with an imperative background.[9]

Motivating examples[edit]

The Haskell programming language is a functional language that makes heavy use of monads, and includessyntactic sugar to make monadic composition more convenient. All of the code samples in this article are written in Haskell unless noted otherwise.

We demonstrate two common examples given when introducing monads: the Maybe monad and the I/O monad. Monads are of course not restricted to the Haskell language, though: the second set of examples shows theWriter monad in JavaScript.

The Maybe monad[edit]

Consider the option type Maybe a, representing a value that is either a single value of type a, or no value at all. To distinguish these, we have two algebraic data type constructors: Just t, containing the value t, orNothing, containing no value.

data Maybe t = Just t | Nothing

We would like to be able to use this type as a simple sort of checked exception: at any point in a computation, the computation may fail, which causes the rest of the computation to be skipped and the final result to beNothing. If all steps of the calculation succeed, the final result is Just x for some value x.

In the following example, add is a function that takes two arguments of type Maybe Int, and returns a result of the same type. If both mx and my have Just values, we want to return Just their sum; but if either mx ormy is Nothing, we want to return Nothing. If we naïvely attempt to write functions with this kind of behavior, we'll end up with a nested series of "if Nothing then Nothing else do something with the x in Just x" cases that will quickly become unwieldy:[1]

add :: Maybe Int -> Maybe Int -> Maybe Int

add mx my =

case mx of

Nothing -> Nothing

Just x -> case my of

Nothing -> Nothing

Just y -> Just (x + y)

To alleviate this, we can define operations for chaining these computations together. The bind binary operator (>>=) chains the results of one computation that could fail, into a function that chooses another computation that could fail. If the first argument is Nothing, the second argument (the function) is ignored and the entire operation simply fails. If the first argument is Just x, we pass x to the function to get a new Maybe value, which may or may not result in a Just value.

(>>=) :: Maybe a -> (a -> Maybe b) -> Maybe b

Nothing >>= _ = Nothing -- A failed computation returns Nothing

(Just x) >>= f = f x -- Applies function f to value x

We already have a value constructor that returns a value without affecting the computation's additional state:Just.

return :: a -> Maybe a

return x = Just x -- Wraps value x, returning a value of type (Maybe a)

We can then write the example as:

add :: Maybe Int -> Maybe Int -> Maybe Int

add mx my = -- Adds two values of type (Maybe Int), where each input value can be Nothing

mx >>= (\x -> -- Extracts value x if mx is not Nothing

my >>= (\y -> -- Extracts value y if my is not Nothing

return (x + y))) -- Wraps value (x+y), returning the sum as a value of type (Maybe Int)

Using some additional syntactic sugar known as do-notation, the example can be written as:

add :: Maybe Int -> Maybe Int -> Maybe Int

add mx my = do

x <- mx

y <- my

return (x + y)

Since this type of operation is quite common, there is a standard function in Haskell (liftM2) to take two monadic values (here: two Maybes) and combine their contents (two numbers) using another function (addition), making it possible to write the previous example as

add :: Maybe Int -> Maybe Int -> Maybe Int

add = liftM2 (+)

(Writing out the definition of liftM2 yields the code presented above in do-notation.)

The Writer monad[edit]

The Writer monad allows a process to carry additional information "on the side", along with the computed value. This can be useful to log error or debugging information which is not the primary result.[10]

The following example implements a Writer monad in Javascript:

First, a Writer monad is declared. Function unit creates a new value type from a basic type, with an empty log string attached to it; and bind applies a function to an old value, and returns the new result value with an expanded log. The array brackets work here as the monad's type constructor, creating a value of the monadic type for the Writer monad from simpler components (the value in position 0 of the array, and the log string in position 1).

var unit = function(value) { return [value, ''] };

var bind = function(monadicValue, transformWithLog) {

var value = monadicValue[0],

log = monadicValue[1],

result = transformWithLog(value);

return [ result[0], log + result[1] ];

};

pipeline is an auxiliary function that concatenates a sequence of binds applied to an array of functions.

var pipeline = function(monadicValue, functions) {

for (var key in functions) {

monadicValue = bind(monadicValue, functions[key]);

}

return monadicValue;

};

Examples of functions that return values of the type expected by the above Writer monad:

var squared = function(x) {

return [x * x, 'was squared.'];

};

var halved = function(x) {

return [x / 2, 'was halved.'];

};

Finally, an example of using the monad to build a pipeline of mathematical functions with debug information on the side:[clarification needed]

pipeline(unit(4), [squared, halved]); // [8, "was squared.was halved."]

The I/O monad[edit]

In a purely functional language, such as Haskell, functions cannot have any externally visible side effects as part of the function semantics. Although a function cannot directly cause a side effect, it can construct a valuedescribing a desired side effect, that the caller should apply at a convenient time.[11] In the Haskell notation, a value of type IO a represents an action that, when performed, produces a value of type a.

We can think of a value of type IO as an action that takes as its argument the current state of the world, and will return a new world where the state has been changed according to the function's return value. For example, the functions doesFileExist and removeFile in the standard Haskell library have the following types

doesFileExist :: FilePath -> IO Bool

removeFile :: FilePath -> IO ()

So, one can think of removeFile as a function that, given a FilePath, returns an IO action; this action will ensure that the world, in this case the underlying file system, won't have a file named by that FilePath when it gets executed. Here, the IO internal value is of type () which means that the caller does not care about any other outcomes. On the other hand, in doesFileExist, the function returns an IO action which wraps a boolean value, True or False; this conceptually represents a new state of the world where the caller knows for certain whether that FilePath is present in the file system or not at the time of the action is performed. The state of the world managed in this way can be passed from action to action, thus defining a series of actions which will be applied in order as steps of state changes. This process is similar to how a temporal logicrepresents the passage of time using only declarative propositions. The following example clarifies in detail how this chaining of actions occurs in a program, again using Haskell.

We would like to be able to describe all of the basic types of I/O operations, e.g. write text to standard output, read text from standard input, read and write files, send data over networks, etc. In addition, we need to be able to compose these primitives to form larger programs. For example, we would like to be able to write:

main :: IO ()

main = do

putStrLn "What is your name?"

name <- getLine

putStrLn ("Nice to meet you, " ++ name ++ "!")

How can we formalize this intuitive notation? To do this, we need to be able to perform some basic operations with I/O actions:

- We should be able to sequence two I/O operations together. In Haskell, this is written as an infix operator

>>, so that putStrLn "abc" >> putStrLn "def" is an I/O action that prints two lines of text to the console. The type of >> is IO a → IO b → IO b, meaning that the operator takes two I/O operations and returns a third that sequences the two together and returns the value of the second. - We should have an I/O action which does nothing. That is, it returns a value but has no side effects. In Haskell, this action constructor is called

return; it has type a → IO a. - More subtly, we should be able to determine our next action based on the results of previous actions. To do this, Haskell has an operator

>>= (pronounced bind) with type IO a → (a → IO b) → IO b. That is, the operand on the left is an I/O action that returns a value of type a; the operand on the right is a function that can pick an I/O action based on the value produced by the action on the left. The resulting combined action, when performed, performs the first action, then evaluates the function with the first action's return value, then performs the second action, and finally returns the second action's value.

- An example of the use of this operator in Haskell would be

getLine >>= putStrLn, which reads a single line of text from standard input and echos it to standard output. Note that the first operator, >>, is just a special case of this operator in which the return value of the first action is ignored and the selected second action is always the same.

It is not necessarily obvious that the three preceding operations, along with a suitable primitive set of I/O operations, allow us to define any program action whatsoever, including data transformations (using lambda expressions), if/then control flow, and looping control flows (using recursion). We can write the above example as one long expression:

main =

putStrLn "What is your name?" >>

getLine >>= \name ->

putStrLn ("Nice to meet you, " ++ name ++ "!")

The pipeline structure of the bind operator ensures that the getLine and putStrLn operations get evaluated only once and in the given order, so that the side-effects of extracting text from the input stream and writing to the output stream are correctly handled in the functional pipeline. This remains true even if the language performsout-of-order or lazy evaluation of functions.

Clearly, there is some common structure between the I/O definitions and the Maybe definitions, even though they are different in many ways. Monads are an abstraction upon the structures described above, and many similar structures, that finds and exploits the commonalities. The general monad concept includes any situation where the programmer wants to carry out a purely functional computation while a related computation is carried out on the side.

Formal definition[edit]

A monad is a construction that, given an underlying type system, embeds a corresponding type system (called the monadic type system) into it (that is, each monadic type acts as the underlying type). This monadic type system preserves all significant aspects of the underlying type system, while adding features particular to the monad.[note 1]

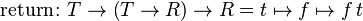

The usual formulation of a monad for programming is known as a Kleisli triple, and has the following components:

- A type constructor that defines, for every underlying type, how to obtain a corresponding monadic type. In Haskell's notation, the name of the monad represents the type constructor. If M is the name of the monad and t is a data type, then M t is the corresponding type in the monad.

- A unit function that maps a value in an underlying type to a value in the corresponding monadic type. The unit function has the polymorphic type t→M t. The result is normally the "simplest" value in the corresponding type that completely preserves the original value (simplicity being understood appropriately to the monad). In Haskell, this function is called

return due to the way it is used in the do-notation described later. - A binding operation of polymorphic type (M t)→(t→M u)→(M u), which Haskell represents by the infixoperator

>>=. Its first argument is a value in a monadic type, its second argument is a function that maps from the underlying type of the first argument to another monadic type, and its result is in that other monadic type. Typically, the binding operation can be understood as having four stages:- The monad-related structure on the first argument is "pierced" to expose any number of values in the underlying type t.

- The given function is applied to all of those values to obtain values of type (M u).

- The monad-related structure on those values is also pierced, exposing values of type u.

- Finally, the monad-related structure is reassembled over all of the results, giving a single value of type (M u).

Given a type constructor M, in most contexts, a value of type M a can be thought of as an action that returns a value of type a. The return operation takes a value from a plain type a and puts it into a monadic container of type M a; the bind operation chains a monadic value of type M a with a function of type a → M b to create a monadic value of type M b.

Monad laws[edit]

For a monad to behave correctly, the definitions must obey a few axioms, together called the monad laws.[12]The ≡ symbol indicates equivalence between two Haskell expressions in the following text.

- return acts approximately as a neutral element of >>=, in that:

- (return x) >>= f ≡ f x

- m >>= return ≡ m

- Binding two functions in succession is the same as binding one function that can be determined from them:

- (m >>= f) >>= g ≡ m >>= ( \x -> (f x >>= g) )

The axioms can also be expressed using expressions in do-block style:

- do { f x } ≡ do { v <- return x; f v }

- do { m } ≡ do { v <- m; return v }

- do { x <- m; y <- f x; g y } ≡ do { y <- do { x <- m; f x }; g y }

or using the monadic composition operator, (f >=> g) x = (f x) >>= g:

- return >=> g ≡ g

- f >=> return ≡ f

- (f >=> g) >=> h ≡ f >=> (g >=> h)

fmap and join[edit]

Although Haskell defines monads in terms of the return and bind functions, it is also possible to define a monad in terms of return and two other operations, join and fmap. This formulation fits more closely with the definition of monads in category theory. The fmap operation, with type (t→u) → M t→M u,[13] takes a function between two types and produces a function that does the "same thing" to values in the monad. The join operation, with type M (M t)→M t, "flattens" two layers of monadic information into one.

The two formulations are related as follows:

fmap f m = m >>= (return . f)

join n = n >>= id

m >>= g ≡ join (fmap g m)

Here, m has the type M t, n has the type M (M r), f has the type t → u, and g has the type t → M v, where t, r,u and v are underlying types.

The fmap function is defined for any functor in the category of types and functions, not just for monads. It is expected to satisfy the functor laws:

fmap id ≡ id

fmap (f . g) ≡ (fmap f) . (fmap g)

The return function characterizes pointed functors in the same category, by accounting for the ability to "lift" values into the functor. It should satisfy the following law:

return . f ≡ fmap f . return

In addition, the join function characterizes monads:

join . fmap join ≡ join . join

join . fmap return ≡ join . return = id

join . fmap (fmap f) ≡ fmap f . join

Additive monads [edit]

An additive monad is a monad endowed with a monadic zero mzero and a binary operator mplus satisfying themonoid laws, with the monadic zero as unit. The operator mplus has type M t → M t → M t (where M is the monad constructor and t is the underlying data type), satisfies the associative law and has the zero as both left and right identity. (Thus, an additive monad is also a monoid.)

Binding mzero with any function produces the zero for the result type, just as 0 multiplied by any number is 0.

Similarly, binding any m with a function that always returns a zero results in a zero

m >>= (\x -> mzero) ≡ mzero

Intuitively, the zero represents a value in the monad that has only monad-related structure and no values from the underlying type. In the Maybe monad, "Nothing" is a zero. In the List monad, "[]" (the empty list) is a zero.

Syntactic sugar: do-notation [edit]

Although there are times when it makes sense to use the bind operator >>= directly in a program, it is more typical to use a format called do-notation (perform-notation in OCaml, computation expressions in F#), that mimics the appearance of imperative languages. The compiler translates do-notation to expressions involving>>=. For example, the following code:

a = do x <- [3..4]

[1..2]

return (x, 42)

is transformed during compilation into:

a = [3..4] >>= (\x -> [1..2] >>= (\_ -> return (x, 42)))

It is helpful to see the implementation of the list monad, and to know that concatMap maps a function over a list and concatenates (flattens) the resulting lists:

instance Monad [] where

m >>= f = concat (map f m)

return x = [x]

fail s = []

Therefore, the following transformations hold and all the following expressions are equivalent:

a = [3..4] >>= (\x -> [1..2] >>= (\_ -> return (x, 42)))

a = [3..4] >>= (\x -> concatMap (\_ -> return (x, 42)) [1..2] )

a = [3..4] >>= (\x -> [(x,42),(x,42)] )

a = concatMap (\x -> [(x,42),(x,42)] ) [3..4]

a = [(3,42),(3,42),(4,42),(4,42)]

Notice that the list [1..2] is not used. The lack of a left-pointing arrow, translated into a binding to a function that ignores its argument, indicates that only the monadic structure is of interest, not the values inside it, e.g. for a state monad this might be used for changing the state without producing any more result values. The do-block notation can be used with any monad as it is simply syntactic sugar for >>=.

The following definitions for safe division for values in the Maybe monad are also equivalent:

x // y = do

a <- x -- Extract the values "inside" x and y, if there are any.

b <- y

if b == 0 then Nothing else Just (a / b)

x // y = x >>= (\a -> y >>= (\b -> if b == 0 then Nothing else Just (a / b)))

A similar example in F# using a computation expression:

let readNum () =

let s = Console.ReadLine()

let succ,v = Int32.TryParse(s)

if (succ) then Some(v) else None

let secure_div =

maybe {

let! x = readNum()

let! y = readNum()

if (y = 0)

then None

else return (x / y)

}

The syntactic sugar of the maybe block would get translated internally to the following expression:

maybe.Delay(fun () ->

maybe.Bind(readNum(), fun x ->

maybe.Bind(readNum(), fun y ->

if (y=0) then None else maybe.Return( x/y ))))

Generic monadic functions[edit]

Given values produced by safe division, we might want to carry on doing calculations without having to check manually if they are Nothing (i.e. resulted from an attempted division by zero). We can do this using a "lifting" function, which we can define not only for Maybe but for arbitrary monads. In Haskell this is called liftM2:

liftM2 :: Monad m => (a -> b -> c) -> m a -> m b -> m c

liftM2 op mx my = do

x <- mx

y <- my

return (op x y)

Recall that arrows in a type associate to the right, so liftM2 is a function that takes a binary function as an argument and returns another binary function. The type signature says: If m is a monad, we can "lift" any binary function into it. For example:

(.*.) :: (Monad m, Num a) => m a -> m a -> m a

x .*. y = liftM2 (*) x y

defines an operator (.*.) which multiplies two numbers, unless one of them is Nothing (in which case it again returns Nothing). The advantage here is that we need not dive into the details of the implementation of the monad; if we need to do the same kind of thing with another function, or in another monad, using liftM2 makes it immediately clear what is meant (see Code reuse).

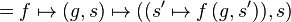

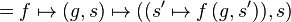

Mathematically, the liftM2 operator is defined by:

Other examples[edit]

Identity monad[edit]

The simplest monad is the identity monad, which attaches no information to values.

Id t = t

return x = x

x >>= f = f x

A do-block in this monad performs variable substitution; do {x <- 2; return 3*x} results in 6.

From the category theory point of view, the identity monad is derived from the adjunction between identity functors.

Collections[edit]

Some familiar collection types, including lists, sets, and multisets, are monads. The definition for lists is given here.

-- "return" constructs a one-item list.

return x = [x]

-- "bind" concatenates the lists obtained by applying f to each item in list xs.

xs >>= f = concat (map f xs)

-- The zero object is an empty list.

mzero = []

List comprehensions are a special application of the list monad. For example, the list comprehension [ 2*x | x <- [1..n], isOkay x] corresponds to the computation in the list monad do {x <- [1..n]; if isOkay x then return (2*x) else mzero;}.

The notation of list comprehensions is similar to the set-builder notation, but sets can't be made into a monad, since there's a restriction on the type of computation to be comparable for equality, whereas a monad does not put any constraints on the types of computations. Actually, the Set is a restricted monad.[14] The monads for collections naturally represent nondeterministic computation. The list (or other collection) represents all the possible results from different nondeterministic paths of computation at that given time. For example, when one executes x <- [1,2,3,4,5], one is saying that the variable x can non-deterministically take on any of the values of that list. If one were to return x, it would evaluate to a list of the results from each path of computation. Notice that the bind operator above follows this theme by performing f on each of the current possible results, and then it concatenates the result lists together.

Statements like if condition x y then return () else mzero are also often seen; if the condition is true, the non-deterministic choice is being performed from one dummy path of computation, which returns a value we are not assigning to anything; however, if the condition is false, then the mzero = [] monad value non-deterministically chooses from 0 values, effectively terminating that path of computation. Other paths of computations might still succeed. This effectively serves as a "guard" to enforce that only paths of computation that satisfy certain conditions can continue. So collection monads are very useful for solving logic puzzles, Sudoku, and similar problems.

In a language with lazy evaluation, like Haskell, a list is evaluated only to the degree that its elements are requested: for example, if one asks for the first element of a list, only the first element will be computed. With respect to usage of the list monad for non-deterministic computation that means that we can non-deterministically generate a lazy list of all results of the computation and ask for the first of them, and only as much work will be performed as is needed to get that first result. The process roughly corresponds to backtracking: a path of computation is chosen, and then if it fails at some point (if it evaluates mzero), then itbacktracks to the last branching point, and follows the next path, and so on. If the second element is then requested, it again does just enough work to get the second solution, and so on. So the list monad is a simple way to implement a backtracking algorithm in a lazy language.

From the category theory point of view, collection monads are derived from adjunctions between a free functorand an underlying functor between the category of sets and a category of monoids. Taking different types of monoids, we obtain different types of collections, as in the table below:

State monads[edit]

A state monad allows a programmer to attach state information of any type to a calculation. Given any value type, the corresponding type in the state monad is a function which accepts a state, then outputs a new state (of type s) along with a return value (of type t).

type State s t = s -> (t, s)

Note that this monad, unlike those already seen, takes a type parameter, the type of the state information. The monad operations are defined as follows:

-- "return" produces the given value without changing the state.

return x = \s -> (x, s)

-- "bind" modifies m so that it applies f to its result.

m >>= f = \r -> let (x, s) = m r in (f x) s

Useful state operations include:

get = \s -> (s, s) -- Examine the state at this point in the computation.

put s = \_ -> ((), s) -- Replace the state.

modify f = \s -> ((), f s) -- Update the state

Another operation applies a state monad to a given initial state:

runState :: State s a -> s -> (a, s)

runState t s = t s

do-blocks in a state monad are sequences of operations that can examine and update the state data.

Informally, a state monad of state type S maps the type of return values T into functions of type  , where S is the underlying state. The return function is simply:

, where S is the underlying state. The return function is simply:

The bind function is:

.

.

From the category theory point of view, a state monad is derived from the adjunction between the product functor and the exponential functor, which exists in any cartesian closed category by definition.

Environment monad[edit]

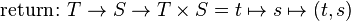

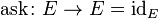

The environment monad (also called the reader monad and the function monad) allows a computation to depend on values from a shared environment. The monad type constructor maps a type T to functions of type E→ T, where E is the type of the shared environment. The monad functions are:

The following monadic operations are useful:

The ask operation is used to retrieve the current context, while local executes a computation in a modified subcontext. As in the state monad, computations in the environment monad may be invoked by simply providing an environment value and applying it to an instance of the monad.

Writer monad[edit]

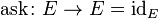

The writer monad allows a program to compute various kinds of auxiliary output which can be "composed" or "accumulated" step-by-step, in addition to the main result of a computation. It is often used for logging or profiling. Given the underlying type T, a value in the writer monad has type W × T, where W is a type endowed with an operation satisfying the monoid laws. The monad functions are simply:

where ε and * are the identity element of the monoid W and its associative operation, respectively.

The tell monadic operation is defined by:

where 1 and () denote the unit type and its trivial element. It is used in combination with bind to update the auxiliary value without affecting the main computation.

Continuation monad[edit]

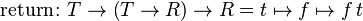

A continuation monad with return type  maps type

maps type  into functions of type

into functions of type  . It is used to model continuation-passing style. The return and bind functions are as follows:

. It is used to model continuation-passing style. The return and bind functions are as follows:

The call-with-current-continuation function is defined as follows:

Other concepts that researchers have expressed as monads include:

Free monads[edit]

Comonads[edit]

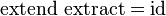

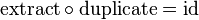

Comonads are the categorical dual of monads. They are defined by a type constructor W T and two operations:extract with type W T → T for any T, and extend with type (W T → T' ) → W T → W T' . The operations extendand extract are expected to satisfy these laws:

Alternatively, comonads may be defined in terms of operations fmap, extract and duplicate. The fmap andextract operations define W as a copointed functor. The duplicate operation characterizes comonads: it has type W T → W (W T) and satisfies the following laws:

The two formulations are related as follows:

Whereas monads could be said to represent side-effects, a comonad W represents a kind of context. Theextract functions extracts a value from its context, while the extend function may be used to compose a pipeline of "context-dependent functions" of type W A → B.

Identity comonad[edit]

The identity comonad is the simplest comonad: it maps type T to itself. The extract operator is the identity and the extend operator is function application.

Product comonad[edit]

The product comonad maps type  into tuples of type

into tuples of type  , where

, where  is the context type of the comonad. The comonad operations are:

is the context type of the comonad. The comonad operations are:

Function comonad[edit]

The function comonad maps type  into functions of type

into functions of type  , where

, where  is a type endowed with amonoid structure. The comonad operations are:

is a type endowed with amonoid structure. The comonad operations are:

where ε is the identity element of  and * is its associative operation.

and * is its associative operation.

Costate comonad[edit]

The costate comonad maps a type  into type

into type  , where S is the base type of the store. The comonad operations are:

, where S is the base type of the store. The comonad operations are:

See also[edit]

- Jump up^ Technically, the monad is not required to preserve the underlying type. For example, the trivial monad in which there is only one polymorphic value which is produced by all operations satisfies all of the axioms for a monad. Conversely, the monad is not required to add any additional structure; the identity monad, which simply preserves the original type unchanged, also satisfies the monad axioms and is useful as a recursive base for monad transformers.

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c O'Sullivan, Bryan; Goerzen, John; Stewart, Don. Real World Haskell. O'Reilly, 2009. ch. 14.

- Jump up^ "A physical analogy for monads". Archived from the original on 10 Sep 2010.

- Jump up^ Eric Lippert. "Monads, part one". Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- Jump up^ Wadler, Philip. Comprehending Monads. Proceedings of the 1990 ACM Conference on LISP and Functional Programming, Nice. 1990.

- Jump up^ Wadler, Philip. The Essence of Functional Programming. Conference Record of the Nineteenth Annual ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages. 1992.

- Jump up^ Hughes, J. (2005). Programming with arrows. In Advanced Functional Programming (pp. 73-129). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. "

- Jump up^ De Meuter, Wolfgang. "Monads as a theoretical foundation for AOP". Workshop on Aspect Oriented Programming, ECOOP 1997.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Moggi, Eugenio (1991). "Notions of computation and monads". Information and Computation 93 (1).

- Jump up^ "Some Details on F# Computation Expressions". Retrieved 2007-12-14.

- Jump up^ "The Writer monad". haskell.cz.

- Jump up^ Peyton Jones, Simon L.; Wadler, Philip. Imperative Functional Programming. Conference record of the Twentieth Annual ACM SIGPLAN-SIGACT Symposium on Principles of Programming Languages, Charleston, South Carolina. 1993

- Jump up^ "Monad laws". HaskellWiki. haskell.org. Retrieved 2011-12-11.

- Jump up^ "Functors, Applicative Functors and Monoids". learnyouahaskell.com.

- Jump up^ How to make Data.Set a monad shows an implementation of the Set restricted monad in Haskell

External links[edit]

Haskell monad tutorials[edit]

- Monad Tutorials Timeline Probably the most comprehensive collection of links to monad tutorials, ordered by date.

- Piponi, Dan (August 7, 2006). "You Could Have Invented Monads! (And Maybe You Already Have.)". A Neighborhood of Infinity. — The most famous "blog post" tutorial.

- Yorgey, Brent (12 March 2009). "The Typeclassopedia". The Monad.Reader (13): 17–68. — An attempt to explain all of the leading typeclasses in Haskell in an elementary way, with monadic functors considered as only one form, best understood by comparison with others: e.g., the more general idea of a "Functor" as something you can map over; "Applicative" functors, and so forth; contains an extensive bibliography.

- Yorgey, Brent (January 12, 2009). "Abstraction, intuition, and the "monad tutorial fallacy"". blog :: Brent -> [String]. WordPress.com. — Opposes the idea of making a tutorial about monads in particular.

- What a Monad is not deals with common misconceptions and oversimplifications in a humorous way.

- beelsebob (March 31, 2009). "How you should(n’t) use Monad". No Ordering. WordPress.com. — Takes a similar point of view, locating monads in a much wider array of Haskell functor classes, of use only in special circumstances.

- Vanier, Mike (July 25, 2010). "Yet Another Monad Tutorial (part 1: basics)". Mike's World-O-Programming.LiveJournal. — An extremely detailed set of tutorials, deriving monads from first principles.

- "A Fistful of Monads". An explanation of Monads, building on the concepts of Functors, Applicative Functors and Monoids discussed in the previous chapter.

- Functors, Applicatives and Monads in Pictures. A humorous beginner's guide to monads.

Older tutorials[edit]

Other documentation[edit]

Scala monad tutorials[edit]

Monads in other languages[edit]

, where S is the underlying state. The return function is simply:

, where S is the underlying state. The return function is simply:

.

.

maps type

maps type  into functions of type

into functions of type  . It is used to model

. It is used to model

, where

, where  is the context type of the comonad. The comonad operations are:

is the context type of the comonad. The comonad operations are:

, where

, where  is a type endowed with a

is a type endowed with a

, where S is the base type of the store. The comonad operations are:

, where S is the base type of the store. The comonad operations are: